A former boomtown’s second life as storyteller in New Mexico

LAKE VALLEY, N.M.

More than 125 years later, Lake Valley, located in the volcanic foothills of the Black Range in southwest New Mexico, is as quiet as a bricked smartphone. The ghost town snaps into view along Highway 27 on the Lake Valley Back Country Byway. The 48-mile drive through ranching and mining country reveals views of several mountain ranges, including the Black Range, the Caballo Mountains, Cooke’s Range, and the Uvas Mountains.

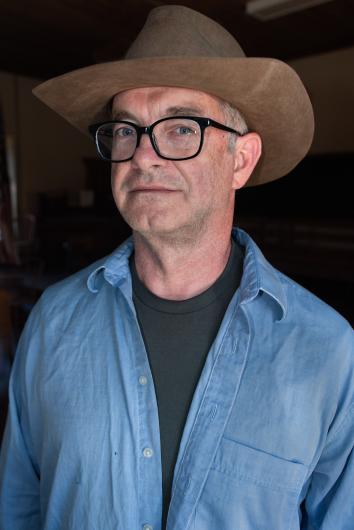

“This area is way off the beaten path,” said Martin Goetz, a Bureau of Land Management archaeologist based in Las Cruces, N.M., during a walk-through of Lake Valley’s restored schoolhouse. “When you come out here, you’re away from the highway. You could be out here for two hours and not a single car will drive by. And you can see for miles out here.”

BLM manages Lake Valley, formally known as the Lake Valley Historic Townsite, about an hour northwest of Las Cruces. On-site hosts maintain the ghost town, which is free and open to the public. You can tour the restored schoolhouse and enter a chapel. Remaining buildings on the townsite have been stabilized to slow further deterioration, which gives visitors a chance to see life as it was before the town’s decline. For those craving a closer look at history, a self-guided tour offers visitors a 45-minute walk to see the structures and encounter the familiar silt of everyday life: scatters of glass, metal, ceramic and wood.

Two peaks—Apache Hill to the north and Monument Peak in the east—overlook the townsite. Volcanic features punctuate hills of grassland and scrub that protect the soil against Chihuahuan Desert winds. Below, more volcanic rock, gravel, shale, dolomites, limestone, granite, and gneiss support the surface on which Lake Valley was built. From high above, clouds print shadows on the rolling hills and then slip away like the silver rush of the 1870s.

Lake Valley is one of several other BLM-managed ghost towns around the country, many of which were established for mining in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In many of these places, prosperity didn’t last forever, turning boomtowns into ghost towns.

In Montana, people can tour the Garnet Ghost Town, which at one point had a population of 1,000 people in the 1890s looking for gold. And in Arizona, a rough trek leads visitors to BLM’s Swansea Historic Ghost Town, where mining for copper began around 1862 and ended in 1912, with a brief revival two years later, closing due to the Great Depression. Miner's Delight, located in Wyoming, is a silent witness to the heyday of that state’s gold mining era. Gold was discovered in the Miner’s Delight area in 1868, and, like other ghost towns, the site offers important clues about the history of the West and mining culture.

“When you look around, you’re constantly seeing stuff. You get the sense of discovery. You’re not looking through a case like in a museum. It’s on the ground.”

Martin Goetz, BLM archaeologist

In New Mexico, there are many stories of when and how silver was found in the Lake Valley area, but one of the first broad public accounts of the Lake Valley discovery appeared in the Engineering and Mining Journal in July 1879. Back then, Lake Valley was a mining camp near a ranch owned by a man named McEvers. Mr. McEvers’s ranch was near Hillsboro, a mining town to the north that was a regular stop along the road through the Black Range.

“Great enthusiasm prevails here regarding the silver deposits at McEver’s [sic] ranch, 10 miles from town,” reported a Mining Journal correspondent based in Hillsboro. “New arrivals from Texas and the north are numerous; a steady stream of teams and men, attracted by our rich mines, is entering our camp daily.”

Those new arrivals encroached on territory already claimed by the Apache, who, as they had with the Spanish, resisted a surge of people. Fresh ambitions for buried wealth persisted as Apache leaders like Victorio and Nana led warriors against the newcomers spreading across the land. It would be a follow-up to previous conflict, when 16th Century Spanish explorers searched for the Seven Cities of Gold.

“The Apaches claimed this region as their own, the heritage of their ancestors, but the white men coveted it, like most of their frontier forerunners … and moved in upon the Indian country with the bark of their rifles rather than as much as an ‘I thank you,’” wrote the historian Conrad Keeler Naegle in The History of Silver City, New Mexico 1870-1886 in 1943.

Then miners hit it big in 1881, revving Lake Valley’s economic engine. The discovery of a vein of silver, nicknamed the Bridal Chamber, began an intense growth of Lake Valley from a mining camp to a town of about 4,000 people.

“The silver apparently was so pure you could just break it off the walls. It was ultra-pure and there was just tons if it,” said Goetz. “Because of that, all of these people came here, and they set up claims all over the place. From that came in the stores and the mining supplies and the clothing stores and everything else that comes in with a town.”

The Bridal Chamber yielded 2.5 million ounces of silver, half of the entire 5 million ounces mined from Lake Valley’s various mines between 1878 and 1893, according to production records from 1895. Profits rolled in with silver at $1.10 per ounce, about $34 today. More people and investment followed, along with demand for housing and places to build.

A 640-pound slab of silver displayed at the Denver Exposition in 1882 drew even more attention and press reports lavishing praise on Lake Valley’s mines, including the legend that candle flames could melt pure silver off the walls.

“When we were brought before a large silver mass, I hit it with my pick; it was soft, and involuntarily my knife came out and I cut it and mashed it, the metallic luster following each test,” a reporter from the Santa Fe New Mexican wrote in June 1882. “The lighted candle being applied, the native silver globules would fall.”

That same year, Lake Valley, which was open around the clock, hired gunfighter Jim Courtright—a.k.a. “Longhair Jim”—as Town Marshal. He brought some order to the town, which in addition to numerous shootings and robberies, grew to have a smelter to process ore, a stamp mill, three churches, a school, two weekly newspapers, saloons, brothels, hotels, general stores and various shops. In 1884, a railroad line extended to Lake Valley, replacing wagons to ship ore.

But beneath the excitement and all the bubbly newspaper accounts, Lake Valley’s demise had been taking form.

Between late 1883 and throughout 1884, expectations of finding another Bridal Chamber overshadowed the work of the Sierra Companies, which ran various mines in Lake Valley. While operators continued to find enough ore, they also struggled to find another pocket like the Bridal Chamber. There were also accusations of stock fraud, which devalued the company. Bad weather, meanwhile, hampered regular ore and supply shipments.

“Shipments have been almost at a standstill during this month on account of the wretched weather and bad roads,” wrote mine manager Fredrick Endlich in February 1884, about efforts to get ore to the nearby town of Nutt, located about 13 miles southeast. The railroad was still under construction at the time. “We are pushing all we can, but the road is strewn with broken wagons and even when we do get the ore away from here, we are not sure when it may reach Nutt.”

Newspapers began reporting less jubilant news. By August 1883, the Mining Journal and other publications described the mines as being “cleaned out” with no new discoveries to rival the Bridal Chamber. Still, operations remained profitable. Until 10 years later, when a change in U.S. monetary policy brought hard times on Lake Valley.

In 1893, the U.S. abandoned silver in favor of gold to back the U.S. dollar. The price of silver fell about 24% over a three-month period that year. Mines began to close all over the territory. With nothing else to drive the local economy, people began to leave.

Then in the pre-dawn hours of June 1, 1895, a combination of wooden buildings and high desert winds set in motion the crowning end of Lake Valley.

Blamed on a man named Mr. Abernathy, a fire started at William Cotton’s saloon and billiards hall near the intersection of Main Street and Railroad Avenue. Fortified by the strong winds, the fire emerged from the saloon, reaching 80 feet across Main Street. Flames entered doorways, bedrooms, halls and offices. The fire made short work of a general store, restaurants, drug stores, a hotel, a barber shop, and the post office.

As if drawn to a magnet, sparks and smoke rushed through the darkness. Firelight made flickering shadow art on the ground. Now two blocks wide, the fire continued southeast, jumping across Clark Street and beyond, until no more buildings were left to burn in that direction. Residents saved what they could, which was very little. Many pets—dogs, cats, and canaries—perished. From afar, the blaze must have looked like an ancient signal beacon.

Inside thirty minutes, the fire, like many Old West boomtowns, came and went in a blaze of glory.

“The rapidity with which the fire spread gave no opportunity to save anything,” reported The Black Range on June 7, 1895, a week after the fire. “C. M. Beals, book keeper for Keller, Miller & Co., on awakening got on pants and slippers and rushed to the office and grabbed an armful of books and after depositing them on the street started back for his trunk, but the fire was ahead of him.”

In July 1896, about a year after the fire, William Jennings Bryan gave his famous Cross of Gold speech, advocating for both silver and gold to back the U.S. dollar. Gold was at $20.67 per ounce. Silver had rebounded slightly to 69 cents per ounce.

But the damage was done at Lake Valley: No rebuilding after the fire. No more mining. More people leaving.

In 1901, a short revival came with mining for manganese shortly before World War I, continuing intermittently until the late 1950s.

“But it wasn’t a boom like it was in the 1800s by any stretch of the imagination,” said Goetz. Instead, the population continued to dwindle. An insurance map drafted by the Sanborn Map Company in August 1902 showed Lake Valley’s business district with zero buildings and the town’s population at 150. The last residents departed in 1994.

The ghost town is in a second act as an observatory to the past.

“When you look around, you’re constantly seeing stuff. You get the sense of discovery,” said Goetz. “You’re not looking through a case like in a museum. It’s on the ground.”

In the 1990s, BLM launched a program to stabilize existing buildings to slow their deterioration. Later, the agency worked with partners to restore the schoolhouse and chapel.

The schoolhouse contains photographs and other evidence of what life was like in Lake Valley, including after New Mexico became the 47th state admitted to the Union in 1912. Along the trails, visitors often encounter milk bottles, mining components, old cars, and toys. And while much of the site is public land, some buildings are marked private property and there is no artifact collection or metal detecting.

The site gets about 10,000 visitors per year, which is about a third of the visitors most BLM sites get in New Mexico. Far from crowded, you can experience Lake Valley at your own pace, as one group experienced during a recent visit.

The visitors, in a white van with Wisconsin license plates, drove up to the restored schoolhouse. After the on-site host gave an overview of the ghost town, they started the self-guided interpretive tour, walking along Keil Avenue, passing the former home of Dr. W. G Beals, a physician. Nearby, an abandoned 1935 Plymouth, missing its straight-six engine, pointed its empty headlights eastward. Advertisements in the 1930s would have promoted the model as capable of going 80 miles-per-hour. The group continued walking to a water tower and coal sorter near a notch in the hillside where a train once came through to the mines.

The group must have learned about Monument Peak, where one of Lake Valley’s last residents, Mrs. Blanche Nowlin, used to walk each morning from her home near the intersection of Keil and Railroad. She died in 1982. And that her next-door neighbors were Pedro and Savina Martinez, Lake Valley’s last residents, who lived in the Bella Hotel building until August 1994.

The group finished their walk and left. Their van passed an abandoned gas station and then turned right on Highway 27 toward Hillsboro, 16 miles north, which with the isolation and quiet at Lake Valley, seemed as far away as the moon.

Derrick Henry, Public Affairs Specialist

Related Stories

- BLM Recreation Sites Available to All: Exploring Accessibility on Colorado’s Public Lands

- Wildland fire module ups fire management and resources

- Dark Sky Week: 12 spectacular BLM stargazing sites

- BLM recreation sites available to all: Exploring accessibility on California’s public lands

- A day on patrol with BLM Arizona Ranger Rocco Jackson