You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

How to Investigate a Wildland Fire

How do we know what caused a wildfire? Some fires are ignited naturally, by lightning storms. Much more often, fires are ignited by people - on average, 85% of wildfires reported nationally each year are human-caused. Sometimes fire causes officially remain undetermined and/or officially under investigation for a long time. What is happening behind the scenes?

Policy requires that all human-caused or likely human-caused wildfires that start or burn on to land managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) be investigated. Wildland fire investigators must have competencies in numerous scientific disciplines, such as fire behavior, fire pattern indicators, and ignition factors – all of which can vary in different areas. Given the varied landscapes of the United States, it is a challenge to maintain standard methods and practices that apply nationwide. They must be based on valid, relevant science, and are therefore constantly being challenged and updated.

That said, there are fundamentals that inform investigation. “Every investigation follows the scientific method,” says Al Crouch, Fire Mitigation Specialist for the Bureau of Land Management’s Vale District in Oregon. “I establish a hypothesis based on evidence, and in order to prove my hypothesis, I have to disprove other possibilities, as well as prove mine. In that way, it’s similar to other scientific and forensic disciplines.”

When a new wildfire is detected and the cause is likely human (usually considered so because of its proximity to human use areas), it’s important to get a fire investigator on scene as early as possible, as fire suppression and the passage of time can destroy delicate evidence. Before heading to the fire, or even on the way, the investigator gets their situational awareness up. What was the weather like in the area around the time of the start? What direction was the wind blowing? What is the fuel type, and how is the area used by people?

Crouch has been investigating fires for more than 20 years, and attests that this documentary evidence gathering, creating a snapshot of conditions around the time of the start, has changed radically in that time. "The internet makes all the difference in the world. Weather and climate models give us information in seconds that we used to have to spend time hunting down. We have access to remote sensing tools, satellite detection, heat detection, aerial imagery – it's all fantastic now compared to what it used to be.”

On scene, the investigator connects with eyewitnesses and gathers testimonial evidence from the incident commander and/or initial attack resources. While testimony is very useful, it is supplemental to the “digging in the dirt” process of fire investigation; fire investigators cannot simply take someone’s word. People may be misinformed or have misperceived, and fire investigators are trained to look for objective facts. Furthermore, sometimes there is no one on scene to talk to, and the investigator must find the relevant information on their own.

The ability to visualize how a fire behaved based on what is left behind relies heavily on experience with active fire. Nick Howell, fire mitigation and education specialist for the Bureau of Land Management in Cedar City, UT, has been investigating fires for 16 years, and credits much of his skill as a fire investigator to his long background in operational firefighting. “The more fire behavior experience you have, the more you’re going to be able to picture what the fire did, how it came to leave these indicators behind. You come in with knowledge of how this fuel type behaves under the weather conditions you had at the time of ignition. The more of that awareness you have, the better of an investigator you’re going to be.”

Fire Investigator Court Gossard of the Boise District Bureau of Land Management office took me out to the field to demonstrate the process he followed on a recent investigation on the grassy public land on the outskirts of Boise, ID, a process that he keeps consistent, despite the variety among the many incidents he investigates.

“I checked the weather from that day, so I knew the wind was coming from that direction,” he says, pointing across the bleak swath of charred brush. “I confirm that by walking around the advancing edge of the fire, looking at the large indicators, the sagebrush and the larger grass clumps. You’ll see where the fire was advancing, and where it was flanking. It guides you into a sort of v-shape, pointed towards the point of origin.”

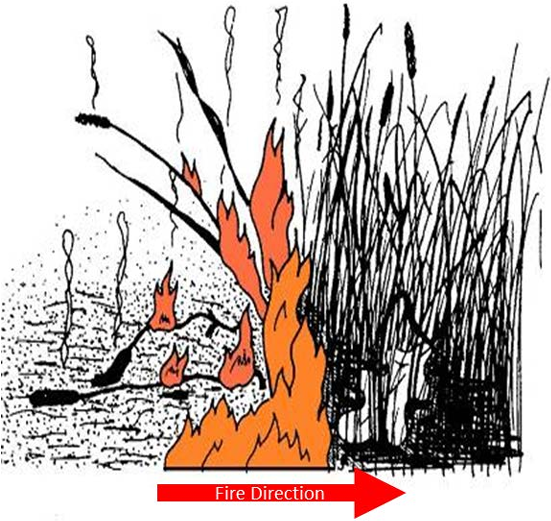

While a patch of blackened ground reveals little to the untrained eye, fire leaves information about its direction and intensity on everything it touches. This includes macro-indicators, like shrubs and trees, and micro-indicators, like strands of grass or pebbles. Following the trail will bring the investigator ever closer to the area of ignition. The ability to follow it is based on science, training, and lots of experience.

Sure enough, following behind Gossard, the burned area gradually narrows, and the fire effects become less severe. We are entering an area where the fire was newer, smaller, and less intense. “I can see that the fire was backing here. A backing fire leaves an angle of char that is level with the slope," Gossard says, indicating a partially burned clump of sagebrush. “And you see the grass stems? A backing fire leaves them pointing in the direction that the fire came from. Now we’re getting to what I identified as my general origin area.”

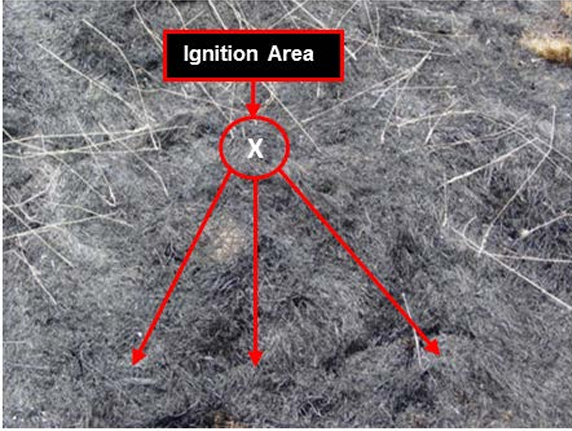

When Gossard establishes the general origin area, he pauses to photograph the scene, ensuring that it’s documented prior to his own intrusion into the area. After that begins the “hands and knees stuff,” the slow, methodical process of observing, marking, and searching the macro and micro indicators, all the way down to seeds that fell from strands of grass.

“At this point, you get down and look at every single grass stem and grass seed and stick. I grid it out. You don’t want to miss a single square inch. I use one of my pin flags and focus on what it’s pointing at, so my eyes aren’t wandering,” Gossard says, holding the pin in front of him and slowly drawing it sideways, a few inches above the ground.

“I mark a lateral in those grass stems. I keep marking, back and forth. The v-shape gets smaller. I’m narrowing it down to the smallest area possible.” Adding complexity, Gossard had by then identified that the fire began with two separate ignitions. "I can see that an advance came out of this area, but also over there. These two were not connected at the beginning. There's a number of things that can cause that.”

Once the investigator has arrived at as small as possible ignition area (or areas) as they possibly can, a variety of tools can help. They may use a metal detector or a magnet, a sifter, or even thermal imaging or electrical currents in their search for the “gold nugget.” Howell reported having recently used a magnet to recover a metal fragment too small to see – nonetheless, impactful enough to start a wildfire. At this stage, finding what you’re looking for also necessitates a lot of knowledge about what you COULD be looking for. Investigators need broad knowledge on systems as complex as powerlines and auto mechanics, because they need to understand the mechanisms behind their causes. Sometimes, this requires collaboration with other subject matter experts.

Is there always a figurative “smoking gun” at the end of this painstaking search? Not necessarily. Sometimes the fire was started by a spark thrown from something outside of the burned area (hence the importance of carefully exploring the perimeter of the fire), and sometimes the source of the ignition is consumed completely. Thus, even while grid searching the origin area in minute detail, Gossard is considering possible explanations based on what else he knows about the area, and what often causes fires that look like this one.

Certain causes come up time and again, and fire investigators become familiar with them. Wheel bearing failures often reach the needed temperature to cause an ignition. On big grass years that follow wet winters, target shooting is a common culprit. Other common causes include various powerline failures, debris burning, escaped campfires, shooting, and fireworks.

“There are no powerlines overhead, but we are right up next to a road, so something vehicle-related is a possibility. There’s a shooting area over there, so shooting is a possibility. Fireworks are also a possibility – they create an ember shower, so you can get multiple ignition areas. So those are three possible hypotheses.”

Gossard did find partially burned remains of a firework outside of the burned area, but stressed that although that supported the firework hypothesis, he was not ready to make his determination yet. “I can’t fully rule out arson at this point, based on what I found. There’s a road nearby, and I have no ignition source inside my ignition areas, both of which are characteristics of arson. At this point, shooting is still a possibility, because the most common ignition source from shooting is lead fragments, and even though I didn’t find any in my search, they could be tiny, and you aren’t going to find lead fragments with a magnet. At this point, shooting, vehicle-related, and arson are dropping down in probability, and the firework hypothesis is starting to rise.”

Eliminated possibilities are referred to as “possible, but not probable,” and the accepted probability for a decision is only 51%, high enough for an investigator to call it “probable.” And if there isn’t sufficient evidence to get any hypothesis to 51%, the investigator may not make a call at all. “Sometimes fires go undetermined. We don’t want to guess. That's not science,” Crouch says.

Once the cause has been determined at 51% or higher, the next matter is, if possible, to identify the person responsible. The searching and processing of evidence serves to determine where and what potential crime occurred, and then helps to identify potential subjects. Fire investigators utilize the same process and reporting procedures even when there is a willing reporting party. If any evidence suggests criminal intent, i.e. arson, law enforcement is involved immediately.

Unwanted ignitions are unintentional the vast majority of the time, but that does not necessarily mean there will be no consequences for the subject. It’s up to a judge or jury to determine if the behavior that caused the fire was negligent or unreasonable, in which case the person responsible could face a criminal fine and pay restitution for damages, or an administrative or civil penalty can be issued, which can be used to recover costs for the damage done by the fire. However, it is not the job of a fire investigator to punish offenders, and such considerations are not part of their fact-finding work. While a fire investigator could be called upon to testify in court, the ultimate decision about consequences is not in their hands.

What about the situations when it is not possible, or simply too costly in terms of time and resources, to identify a responsible party? According to Howell, a subject is positively identified only about half the time. Is there still value in the investigation? There is indeed – understanding what causes fires in a particular area provides excellent information for designing fire prevention campaigns. “If I investigate 20 fires and determine that 18 of them were escaped campfires, that is a clear way to inform prevention,” Crouch says. “Cost recovery for damages is good for the taxpayer, but at the end of the day, fire investigation is more about prevention than prosecution.”

Roadside fires are an example of fires that can be difficult, or prohibitively onerous, to trace back to a responsible party. Myriad vehicle failures can cause roadside fires, such as blown tires or steel belts, dragging chains (evidenced by a little line of fires), or exhaust failures (pieces of catalytic converter that come flying out of the muffler), and by the time the fire investigator arrives on scene, the vehicle in question may be long gone, the driver perhaps not even aware of the trouble they have caused.

How do we tackle the problem of roadside fires? Crouch’s district has found through fire investigations that vehicle malfunctions, off of state, county, and interstate transit corridors, are their most common culprits. “We have to be creative, because the corridors themselves are not our jurisdiction, so we have a lot less control. If fires are starting in BLM campgrounds, that’s an easier answer,” Crouch says. Crouch’s district has tackled the challenge by producing digital and print products to educate the public on how vehicle fires cause wildfires, and what they can do about it as vehicle owners. They table at public events, issue public service announcements on the radio, and leverage partnerships to get the word out.

“A great initiative we’ve worked on is partnering with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife at the road check stations on the state border,” Crouch says. “Vessels crossing the Snake River are being checked for invasive species. We can take that same opportunity to check that vehicles’ bearings are greased, tires are inflated, and no chains are dragging. It's an opportunity not only to check vehicles, but also to raise awareness and make contact with the public.”

Other jurisdictions have adopted preventative initiatives in partnership with state departments of transportation like mowing broad swaths along roadsides before the grass cures, which prevents many ignitions outright and keeps those that occur much smaller.

The results of fire investigations have been used to inform such broader scale efforts as Arizona Interagency Wildfire Prevention’s One Less Spark, One Less Wildfire campaign, and BLM Nevada's Spark Safety, Not Wildfires campaign in partnership with Maverik, which recently was awarded a Silver Smokey Bear Award.

It’s said that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and that’s key when it comes to fire prevention, because a pound of cure simply may not be available. “Communities are continuing to grow, especially out west,” says Howell. “There are more human-caused fires than ever before. The workload for fire investigators is daunting. The best thing we can do is double down on prevention.”

What challenges do these seasoned investigators recognize in their field? The good news is that awareness is growing about how important this work is. However, Crouch says, “nationally, there are very few of us. Even in the BLM, which has the most robust program in the country, almost everyone is doing it as a collateral duty. Lots of people train, but few people actually do it on a regular basis. And you do need to do it consistently,” Crouch says.

Howell and Crouch are prime examples of the many hats worn by many fire investigators; investigations make up about one third of Crouch’s work, while Howell manages six distinct programs, of which fire investigation and trespass is only one. Gossard is a rare breed as a standalone fire investigator, doing it as his full-time job, a specialization justified by the huge number of human-caused fires to investigate in a place where so much flammable public land lies just outside of a major city; his annual investigation count is routinely over 100.

Furthermore, beyond the drive for scientific accuracy and relevancy, there is an increasing stringency on legal standards for investigations. “We are being challenged on a lot of cases. Legal standards, reporting standards, training and record keeping standards, are all a lot higher than they used to be," Howell reports.

Fire investigators need to keep their skills sharp, as well as stay up to date on new methods, tools, and best practices. To that end, the Bureau of Land Management held the 2024 Fire Investigation and Trespass Summit in Reno, NV this spring, welcoming fire investigators from all over the country.

“Solving the mystery is the fun part, but a lot of other skills are involved. From the day you start an investigation to the day you’re finished with it, you might be looking at 18 months. You need good interviewing skills and to be able to talk to people. You need to be able to do research and follow leads. Some new people are turned off by how much report writing, research, math, and analysis are involved. But there’s a hook once you get started. It’s rewarding work,” Howell says.

Rebecca Paterson, Public Affairs Specialist, BLM Fire

Related Stories

- On the Arizona Strip, Now is the Time for Fire and Fuels Work

- Aerial Sagebrush Seeding Helps Restore Robertson Draw Fire Burn Area

- Long-term partnership between BLM Fire and United States Air Force builds national firefighting capacity and accomplishes critical fuels work

- Enhancing Wildland Fire Response: Modernizations to Wildland Fire IT

- Recreate Responsibly with Fire