“Laundress” – Mrs. Nash and Wrung-Out History

A journey of knowledge and uncovering a mystery started with a trip to a local flea market in Rapid City, South Dakota. I bought a small used book called “Black Hills Believables" by John Hafnor. I didn’t think anything of it at first but learning about the stories within would occupy my interest for months to come. I picked it out because I hadn’t seen anything like it before. This isn’t to say I haven’t seen books like it before, every local area has its own stories, especially the Black Hills. But I haven’t seen too many that include outside “the hills” locations such as the Badlands, Bear Butte, and Fort Meade. Inside, it had all the standard stories of firsts and lasts, famous lives and famous deaths but one story stood out in particular and led me down a deeper rabbit hole.

As I was reading, there was a tale about the local Old Post Cemetery which is on the historic grounds of Fort Meade managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) South Dakota Field Office. At the very end of the story, it mentioned the existence of an unknown grave, simply labeled “Laundress” which the author had heard speculation actually belonged to a “Ma” Nash. What made this person so intriguing is that “Ma” Nash was assigned male at birth and lived as a woman amongst the soldiers of the 7th Cavalry.

This is how "Black Hills Believables" (1983) characterizes her:

"Another grave, marked simply "Laundress" is believed to belong to "Ma" Nash. She had been connected with the laundry business of one fort or another for years and had been married more than once. "Ma" Nash seemed ordinary enough, except she wore a veil and had insisted that when her time came, she be buried without a fuss. Death came in 1879. People may have wondered what to put on the gravestone, for it turned out that "Ma" Nash was really a man!"

As someone working in cultural resources, it is very rare to be able to associate an everyday person with a famous event as well as an archaeological site. It’s rarer still to have that person seemingly parallel our current understanding of gender. From a modern understanding, “Ma” Nash seems to fall under the umbrella of transgender identities. It’s a topical social and political talking point, and one I am personally invested in being connected to the LGBTQIA+ community. I wanted to figure out if the claim that this “unknown” grave on BLM managed land did really belong to “Ma” Nash. I felt I could do some good reconciling a historical wrong and bring some attention to a woman at a time when more people are looking to the past to show that trans people have always been a presence in history. I wanted to understand how she lived, how she died, and how time seemed to pass her by not dignifying her grave with a name.

The first question was, who was “Ma” Nash? While doing a web search of the name yielded curated articles and old newspaper scans, I wanted to do something more “old-fashioned” and see if I could find any physical write-ups to compare with what I read in Hafnor’s book. I ended up picking up “Soap Suds Row: The Bold Lives of Army Laundresses 1802-1876” by Jennifer Lawrence.

In Chapter 8 titled “Dirty Laundry” she leads with the topic of a Mrs. Nash (with no mention of the title “Ma”):

"Mrs. Nash is perhaps the most famous laundress of them all. Mrs. Nash, whose first name is not recorded, was nicknamed "Old Nash" and followed the Seventh Cavalry for a number of years. She had worked for Elizabeth Custer, wife of George Armstrong Custer, and earned admiration with the meticulous care she gave laundry...”

In terms of famous historical figures of the Black Hills, one of the more famous (or infamous) figures is General George Armstrong Custer. And here Mrs. Nash was, working and tending alongside the Custer family, specifically Elizabeth Custer, his wife. Lawrence continues saying Mrs. Nash was married two times prior to her final husband. While information seems scarce, we know he was a man from the army who stole all her money and left her without formally divorcing. The second husband was also in the army and was the one who brought Mrs. Nash out to the Dakota Territory to Fort Abraham Lincoln. Since, as customary with army laundresses, Mrs. Nash followed the unit she was with. However, this husband also deserted the army, stole her money, and disappeared. There is confusion from sources on who the first and second husband actually was, whether it is Mr. Nash or a Mr. Clifton (or Clifford) is switched both from news articles at the time, and in articles today. Despite the second marriage failing she married yet again to Corporal Patrick Noonan in 1873 after arriving at Fort Abraham Lincoln.

Sadly, during her time at the fort illness befell her. Mrs. Nash’s condition worsened while Noonan was away with the cavalry. She insisted to the other laundresses that when she was to die that she be buried without delay. To be buried quickly, with no preparations – against all customary treatment of the dead. To the other laundresses this was unthinkable, Mrs. Nash was beloved. She was much more than a laundress, she made pies, fixed uniforms and was considered "the most popular midwife in the garrison.” They wanted to honor her in death as she had honored them in life.

According to the local Bismarck Tribune, she died at 5 a.m. on Oct. 30, 1878, at Fort Abraham Lincoln. Upon her death the other women decided to go against her wishes and give her a proper burial. While conducting preparations the other woman discovered that Mrs. Nash possessed male anatomy from birth and from there, the media at the time went wild. She became a national spectacle.

The Bismarck Tribune made Mrs. Nash’s death front page the week after her passing. This is among one of the first contemporary accounts of her death. They ran a headline on Monday, Nov. 4, 1878, which was based on an earlier article in the Chicago Times titled “The Mystery of Mrs. Noonan” – A remarkable post-mortem discovery at Fort Abe Lincoln – A Sexual Imposition” The article comments on Nash’s abilities as a Laundress, her looks, her ethnicity (she was a Mexican woman) and her husband’s sexuality. It ends ominously stating: "Corporal Noonan is in the field with the Seventh Cavalry and will probably swear when he hears the sad news."

Trying to follow-up on this account is difficult. I haven’t found any copies of the Chicago Times from this period, nor copies or accounts by the medical examiner of the fort or any personal writings from the priest who provided last rights.

However, what is well-recorded is within a week of his return to the fort the local newspapers were hounding Corporal Noonan. They asked him how he couldn’t have known who he married was not born female. Noonan was constantly harassed with jeers and degradation. He insisted they were trying for children. In his shock and pain, he went AWOL and hid in the stables of the fort where he was still pursued by reporters. After an interview, Corporal Noonan shot himself in front of his fellow soldiers only after one of them made yet another comment regarding his relationship with Nash. It is mentioned he was to be buried at the North Dakota fort but later he was moved to Custer National Cemetery to join the rest of his ill-fated regiment and it’s where his plot rests today … but not Mrs. Nash’s.

Where was Mrs. Nash buried?

While robust, Lawrence’s work has no conclusion to the Mrs. Nash story. Other sources leave her passed on with the attention being paid to her husband and not to her. Upon looking into the historical papers at the time it becomes clear as to why. For months after Noonan’s death, almost all the attention, and the ire of the public, was directed onto him.

Mrs. Nash was scarcely talked about in comparison to Noonan. From November of 1878 to January of 1879 papers across the United States such as the Bismarck Tribune, Sioux City Journal, The Inter Ocean, The Chicago Tribune, and the New York Herald (to name a few) ran articles about Nash and Noonan.

The most popular articles are ones speculating on Noonan, lamenting or applauding his death, and picking apart the physical aspects of Mrs. Nash trying to dissect every aspect of her known life and existence. But it was sparse and lacked any real investigation. Mrs. Nash kept her secrets close and took her story to her grave. So little was known about her life before the army, that in an attempt to “expose” her a seance was performed and reported on by the papers at the time. This left a string of speculation, rumors and falsehoods which still poison some of the literature around her today as the sensationalism created erroneous accounts of her life in droves.

Modern articles have done little better expanding on Mrs. Nash’s life or death than the ones back then. An article run in 2012 by the Bismarck Tribune mentions her date of death as November 4, 1878, and that her second husband was Nash. Which is partly incongruous with the first source article from the same newspaper. November 4 is when the first Bismarck Tribune article was published, not when she actually died. In the original article it’s written that she died on October 30. However, the new article seems to have information that Clifford was the first, not the second husband something that was previously corrected by the Tribune.

But the question still remained, where was Mrs. Nash buried?

In a recent article about Nash from 2023 by the web outlet LGBTQNation the write-up concludes:

"Mrs. Nash and Noonan were both buried at Fort Lincoln with proper military burials. Once the fort closed, Nash was relocated to an unmarked grave for civilians in St. Mary’s Cemetery, while her last husband was reinterred at Custer Battlefield National Cemetery."

While this seems conclusive, I can't properly verify that claim because, there are no sources citing this information and it seems contradictory to other, earlier sources. There is a Noonan listed in the cemetery records of St. Mary’s however, this appears to be another Noonan based on a contemporary article by the Bismarck Tribune. A dead end. According to the service records from Fort Abraham Lincoln it is recorded that Noonan was buried at the fort, marking "Cpl. John Noonan, 7 US Cavalry, died of gunshot wound, Nov. 30, 1878” yet within the months prior and after there is no actual mention of Nash or any solider or citizen military burial by that name or a related one.

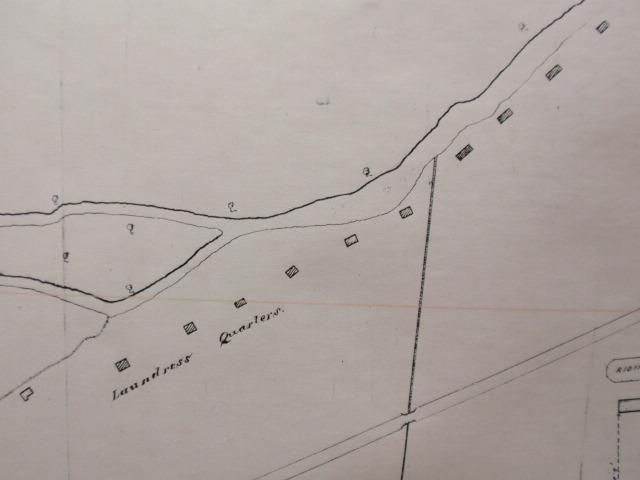

With an interest in archaeology and local history, I went to the Old Post Cemetery to see the “Laundress” grave myself. As mentioned in the beginning the area is open to the public and actively managed by the BLM.

Would you believe me if I said that the burial at the Old Post Cemetery on Fort Meade labeled as just “Laundress” doesn’t exist? I checked. Then after I checked, I asked other local archaeologists for confirmation. It was just another part of the myth making around Mrs. Nash. As true as the seances had been 150 years prior. Just another layer in the transformation of Mrs. Nash from person to historical myth.

There is however a real grave with the name “Annie Franklin, Laundress.” Now I knew Annie was here because I’ve been involved in archaeological excavations of Fort Meade’s Soapsuds Row – the historic area of the fort where the laundresses lived and worked. What I forgot, up until this moment, was that nothing is known about Annie. Her birth, her death, where she was from and everything else about who she was. Frankly, we don’t know nearly as much about the lives of laundresses in most frontier forts as compared to the army. The historical record didn’t capture their stories.

To return to the beginning, about reconciling a historical wrong and bringing some attention to a woman history labeled as just “Laundress”. I can’t say I feel any clearer of the location where Mrs. Nash is buried, or if it matters. While it seems likely that she would be at Fort Abraham Lincoln and moved from there, it’s never really confirmed by papers from the time. She certainly isn’t at Fort Meade like the book said. Even if I found that unknown “Laundress” grave, would it really be any different from Annie Franklin’s?

We know nothing about Annie except her name, from all my work looking into Mrs. Nash we know little about her that we can confirm is accurate. It's tempting to solve puzzles, and to shine a light on a forgotten past and find satisfying answers from written histories. Putting a name to a number or a title brings it new life and provides a comfortable closure to my brain, but the historical record certainly doesn’t seem to care who Annie was or where Mrs. Nash is and a part of me feels, at the very least, Mrs. Nash didn’t care either. She wanted to be buried as she was, to be laid to rest simply. To me, the idea of an unspecified grave of “Laundress” sparks curiosity because anyone could be buried there. Does a name change so much that Annie Franklin provides any difference? Mrs. Nash may live on in folklore, but Annie barely lives on in history. As I said, wherever Mrs. Nash’s physical body is doesn’t matter too much to me anymore. Her story, as tragic as it is, is one we at least know partially, how many Annie Franklin’s are in history? Their stories contain as many multitudes as Mrs. Nash’s yet all we know goes to a single word, the same word that started this, “Laundress.” That’s what cultural resource work and the excavations at Soap Suds Row are for, that’s the history we need to protect and preserve so that we can find out more. When we do that, we can start connecting with the people in the past and bringing them new life though our understandings filling in the blanks and dispelling myths built on the lies of time.

Every laundress was a person, with their own story and the grave at Fort Meade stands for a laundress but it could be any “laundress”.

Mrs. Nash was a laundress; Annie Franklin was a laundress. For me, I answered my questions and have found new ones.

Catherine Oberheim, Archaeologist

Attachments

Related Stories

- Tackling the Legacy of Orphaned Wells: The Federal Orphaned Well Program in Action

- Secretary Deb Haaland visits with Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps crew working to stabilize Lowry Pueblo

- Full Circle: BLM and Special K Ranch Plant Native Sagebrush Seedlings

- BLM Archaeologists Tell Ghost Town Story On Nevada Day Weekend

- From the Ground Up: Small Crew Makes Big Impact