You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

50 years sharing frustration and joy have bonded Alaska Natives and BLM employees working together on ANCSA land conveyances

It’s been 50 years since the largest land claims settlement in U.S. history passed and helped give the Bureau of Land Management the largest land transfer program in the country. It has created relationships like no others between BLM Alaska employees and the Alaska Native people they serve, many for most or all of their careers.

As this 50-year land transfer story begins its final and perhaps most complex chapter, the bureau is relying on those relationships more than ever to work with Alaska Native Corporations to reach a positive conclusion and fulfill this significant commitment to Alaska Natives.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971, or ANCSA, settled aboriginal title in Alaska by extinguishing title and directing the BLM to transfer millions of acres of surface and subsurface rights to the private ownership of regional and village Alaska Native Corporations, or ANCs. As opposed to the previous reservation approach in most of the U.S., Alaska Natives and their allies negotiated for the provisions in ANCSA that took a very different direction without replacing or diminishing other rights.

The first legislation of its kind in the United States, the Act authorized conveyance of approximately 46 million acres to state-chartered ANCs and individuals. Eventually, 12 regional, 211 village, 9 Native group, 4 urban, 5 former reserve, and 1 joint venture, for-profit corporations were established. The corporations selected lands from within their respective common ancestral boundaries to preserve their heritage and protect their culture while pursuing economic opportunities and self-determination for their shareholders.

“ANCSA is proof that Congress recognized that the Alaska Native people had the right and responsibility to manage their own affairs and determine their own destinies,” said BLM Alaska Land Law Examiner Christy Favorite.

After the law’s passage, there was a flurry of applications from the new ANCs and, despite having conveyed about 96% of ANCSA entitlements in 2021, making it all happen responsibly continues to be BLM Alaska’s monumental and complex task. How big is that task exactly? It means surveying, adjudicating, reviewing, legally transferring rights, and confirming titles to land that combined equals the size of Washington state, most of which lacks roads or infrastructure of any kind.

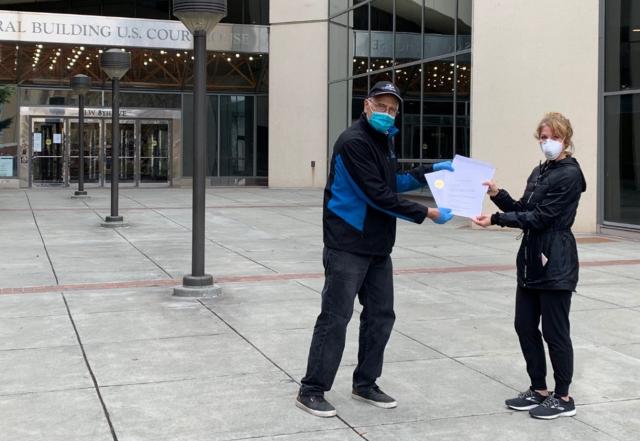

It can be a frustratingly long process both for BLM professionals and recipients who have worked decades together to ensure Alaska Native people get clean title to the lands they’ve selected. It can also be quite emotional for everyone involved when a final land patent is issued. Like in the case of like Vice President for Cultural Resources at Chugach Alaska Corporation John Johnson who recently received title to a cemetery site after more than 40 years.

“It keeps us vibrant to stay connected,” said Johnson, whose grandmother was from the village of Nuchek (Nuuciq), a major trade center in the early days of the Russian colonization. “Our ancestors have been buried in the hills for the last 4,000 years.”

“This project has gone on since the ‘70s,” said Johnson, who now dedicates his time to reconnecting his people with their cultural historic and cemetery sites conveyed through ANCSA. “Other people who make this possible -- surveyors, adjudicators; they all help make this process come along,” he said, recalling BLM and Bureau of Indian Affairs employees by name, including one who passed away.

“We see folks at the ANCs tear up because they’re getting that land back for their elders, which has deep meaning for them,” said BLM Alaska Land Law Examiner Judy Kelley, who recalls seeing many of these applications in the early 1970s. “When you feel that emotion, it drives us to finish what was started decades ago.

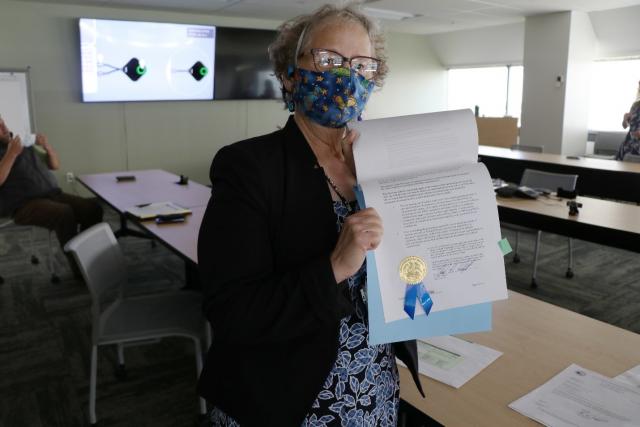

“To know that your name is attached to that file for all of eternity, that’s what it’s all about. You’re a part of history, engraved in the record,” said Kelley. “Every selection file, every village entitlement, every historical cemetery site that you patent, close, or reject, it makes a difference, and you’re contributing to the overall settlement that affects people and affects their lives.”

Favorite, who has spent two-thirds of her life working on ANCSA-related conveyances and said the required application-to-conveyance time is trying but often necessary to avoid catastrophic problems in the future. Assuming the basic application documents are accurate, politics, conflicts, and potential new laws and entitlements can cause unforeseen problems midstream. To mitigate delays, BLM Alaska specialists research title history, precedent set by Interior’s Land Appeals Boards, court decisions, agreements, and competing selections to ensure conveyances are done right the first time.

“Even if it's just five acres, a small conveyance can be the most complex and politically challenging,” Favorite said.

It’s now been 50 years of federal staff and land recipients working together to transfer millions of acres from the federal estate back to the original occupants. Meeting the requirements of the various land laws continues to call for deliberate and meticulous work that adds up to much more than acreage on a spreadsheet or lines on a on a map.

For a village that can now legally develop economic drivers on the lands of their ancestors, having title to that land can literally mean creating a sustainable future for themselves and future Alaska Natives.

“They (the lands) help us survive culturally and economically,” Johnson said. “It helps us give the next generation a fighting chance.”

The true meaning of these conveyances is not lost on Favorite, who smiled and said, “It’s been a good way to spend two-thirds of my life.”

Melinda Bolton, Public Affairs Specialist

Related Stories

- BLM Recreation Sites Available to All: Exploring Accessibility on Alaska’s Public Lands

- A boatload of recreational opportunities

- Exploring the Campbell Tract Special Recreation Management Area: Flora, fauna, and volunteer opportunities

- Far more than a few beavers

- Love letters from our public lands: Wolf Run Cabin