You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

From slave to landowner: The grit and gumption of Letitia Carson

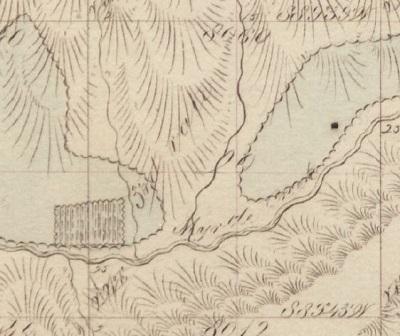

Photo by Jacob Holden, BLM, Feb. 2021.

From slave to Oregon Trail traveler to Black landowner, the story of pioneering Oregon homesteader Letitia Carson is an inspiring one—with a BLM connection.

“What happens to a dream deferred?” asked poet Langston Hughes famously in the 1950s. “Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?” In Carson’s case, nearly a century earlier, her dream of freedom and property ownership was ultimately realized—but only after decades of grit and gumption.

Born a slave in Kentucky around 1815, Letitia Carson moved to Oregon with David Carson—the father of her children and possibly her owner or former owner—in 1845, following the Oregon Trail. As a Black woman and as either a slave or former slave, she could not own land in the Oregon Territory. More than that, her very presence was not welcomed.

A year earlier, in 1844, Oregon’s provisional government amended a law that prohibited slavery, adding a clause that provided slaveholders time to take their slaves out of the territory and free any slaves who remained.

Those who stayed, however, were required to leave the territory after two years if male and three years if female. Any free Black man or woman who refused to leave would be subject to physical lashing.

A more lenient punishment was instituted, and the law was rescinded by voters in 1845, but its effect remained—free Blacks were not encouraged to move to Oregon.

Despite this, David, Letitia, and their children soon settled on a 640-acre land claim in Benton County, which was reduced to 320 acres in 1850 likely due to their unwed status. (The law provided 640-acre tracts for married couples.)

By that time, Oregon had enacted another exclusion law that made it illegal for anyone of Black ancestry to enter or reside in the territory, excepting anyone already present—including Carson and her children.

After David Carson’s death in 1852, and despite her unclear legal status, Letitia Carson took action. While she attested that David had said he would make her “his sole heir or he would give me his entire property,” this was not found in writing and she was denied his estate.

Following several subsequent legal actions, she eventually recovered a modest financial settlement from the estate for herself and the couple’s children.

But land ownership was still legally out of her reach.

Statehood changed little. In 1859, Oregon became the first free state with a Black exclusion clause in its constitution to be admitted to the Union. Oregon’s Bill of Rights not only prohibited Black presence in the new state, but also outlawed Black property ownership and legal contracts.

President Abraham Lincoln is widely known for the Emancipation Proclamation issued in September 1862, but an act he signed into law a few months earlier enabled Carson and many other African Americans to claim—and eventually own—government land in Oregon and throughout the American West.

The 1862 Homestead Act allowed adult heads-of-household—male or female—the opportunity to claim 160 acres of surveyed government land in the West.

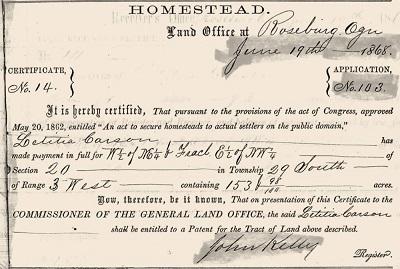

from Oregon Secretary of State website.

After living on the land for five years and adding improvements like a house, barn, or cultivated field, a claimant could pay a small registration fee and own the land free and clear. If they wanted to own it more quickly, they could live on a claim for six months, make small improvements, and pay the government $1.25 an acre.

Unlike Oregon’s constitution, this law did not exclude Black people from land ownership. The Homestead Act of 1862 was exactly the opportunity Carson needed—it was her shot at homesteading her family’s own plot of land.

This opportunity came at a cost, however. The land in the American West offered to U.S. citizens through the Homestead Act had already been occupied for hundreds of years—it was the longstanding, ancestral home of dozens of American Indian tribes, and homesteaders were dispossessing them with each claim filed.

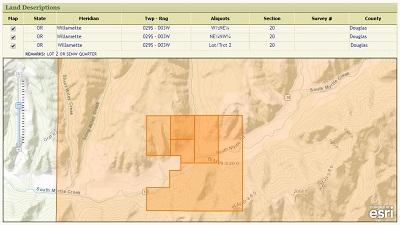

When the new law was enacted, Carson and her family were living in Douglas County. At the General Land Office in Roseburg, Oregon, on June 17, 1863, she filed a Homestead Act claim for just under 154 acres on South Myrtle Creek in the county.

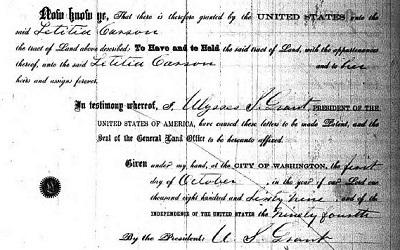

President Grant. BLM General Land Office Records,

Serial Patent ORRAA008939, Letitia Carson.

On Oct. 1, 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant certified Carson’s claim, making her the only Black woman in Oregon to successfully secure a claim, according to the Oregon Secretary of State website.

Carson’s claim was also one of the first 71 ever certified in the U.S., of a total 1.6 million. Under her care, her homestead soon grew to include a house, barn, smokehouse, and apple orchard. She would live there until her death in 1888, and she remains close today—she is buried a few miles away in the historic Stephens Cemetery.

Today, historic Government Land Office documents curated by the BLM help provide a detailed record of her historic accomplishments. They include land descriptions, digitized survey maps, and Carson’s digitized patent authorized by President Grant.

Records, Serial Patent ORRAA008939, Letitia Carson.

The BLM also tells the story of Oregon Trail immigrants—including the many slaves and former slaves who traveled it—at sites nationwide, including the National Historic Oregon Trail Interpretive Center near Baker City, Oregon.

Current plans call for Carson's story to be featured in a new exhibit entitled "Extraordinary Women of the Oregon Trail," scheduled to open at the site in June of 2021.

Carson’s ranch site is still farmed today, and the forested creek that passes through her original claim is named in her honor. Letitia Creek, with headwaters on BLM-managed public land in southwest Oregon, flows into South Myrtle Creek about halfway between Crater Lake and the Pacific Ocean.

It remains a tangible, local connection to an important chapter in our nation’s history—the realized dream of a freed slave to own land in Oregon.

Photo by Jacob Holden, BLM, Feb. 2021.

Greg Shine, Interpretive Program Specialist

Related Content

Learn more! Sources for this article include:

Related Stories

- Overcoming challenges to move the BLM forward: Nikki Haskett

- A former boomtown’s second life as storyteller in New Mexico

- Fueling the frontlines: State program accelerates wildland firefighter training

- Local volunteers are the rock of the San Juan Islands National Monument

- BLM Archaeologists Tell Ghost Town Story On Nevada Day Weekend

Office

777 N.W. Garden Valley Boulevard

Roseburg, OR 97471

United States