Foresters aim to make Whitebark pine more resistant to insects and diseases in Montana-Dakotas

Listen

Subscribe

Related Content

Whitebark pine is a threatened species of conifer that grows primarily in three states and western Canada. Foresters and researchers have been working for years to deal with pests like the mountain pine beetle, and diseases like white pine blister rust. Emily Guiberson (photo, above) has worked on saving and restoring Whitebark pines most of her career in southwest Montana. Now the lead Forester for BLM's Montana/Dakotas State Office, we talk with her about recent investments from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Transcript

NARRATOR (DAVID HOWELL, Senior Communications Specialist):

Whitebark pine, listed as a threatened species of conifer in 2022, grows primarily in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and up into western Canada. The southern reach of its habitat is the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, an area surrounding Yellowstone National Park that includes many federal and state agencies, tribal governments, and non-governmental partners.

I'm David Howell and you're listening to “On The Ground, a Bureau of Land Management Podcast.” When the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law was passed in 2021, BLM invested in ecosystem restoration projects nationwide, including projects in whitebark pine forests in these three states. Emily Guiberson started her career in Dillon, Montana and is now the lead Forester for BLM’s Montana/Dakotas State Office. And the first question I asked her was, “Why is whitebark pine a tree we need to care about?”

EMILY GUIBERSON (BLM State Lead Forester, Montana/Dakotas): So, whitebark is a high elevation five-needle pine tree species that is very important for ecosystem functions. They're at the highest elevations, and so the shade is protecting the watershed. It’s helping the snow come off slower so that it's more of a trickle instead of just all at once.

It's also very, very important food source for different wildlife. The Clark’s Nutcracker is one of the primary seed dispersers. Grizzly bears are -- bears in general -- it's a high-calorie food intake, as they're going into hibernation. It's highly sought after by wildlife species.

NARRATOR: It’s also a species that is under attack by a variety of pests and diseases. One pest is the mountain pine beetle, an insect the size of a grain of rice which, in large numbers, can kill large stands of trees, and that makes the trees susceptible to large, stand-replacing wildfires. Another is an invasive fungus called white pine blister rust, which can kill branches and inhibit a tree’s ability to produce cones and seeds. And Emily says that there are other concerns besides these two, including warming temperatures related to climate change, and the fact that periodic smaller fires have been excluded from the landscape.

GUIBERSON: We were also seeing multiple beetle hatches in a year, which was not anything that we had seen previously. Additionally with that, we were seeing them get higher in elevation than they had previously because usually at those elevations that you find the white bark, there's cold enough temperatures that if there are beetles there in small populations. They were not able to go big like they did when we had kind of the tail end of those big droughts that we were seeing in 2008, 2009.

HOWELL: Yeah.

GUIBERSON: So it kind of all is, like -- they're separate, but they're all tied together.

HOWELL: And these are a fairly slow growing tree if I remember right.

GUIBERSON: Very, very slow growing. Very slow growing. The oldest one that I've ever cored in southwest Montana, was probably… We couldn't get to the inside; we were still, you know, a ways off at the end of the very center, but it was over 350.

HOWELL: Oh, several hundred years old.

GUIBERSON: Mmm-hmm.

HOWELL: Yeah, okay.

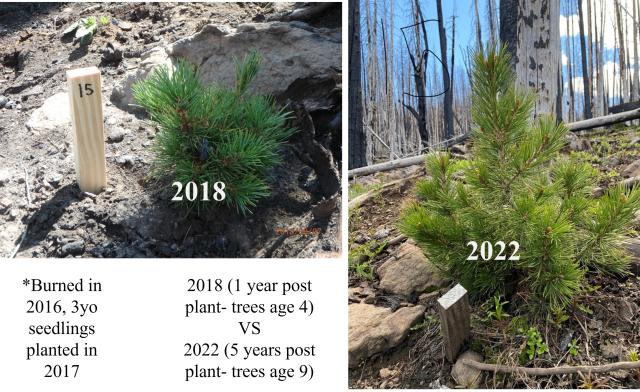

NARRATOR: Which means that if a wildfire comes through an area already weakened by disease or beetle damage, it may be a century or more before new whitebark pines will get large enough to protect an area from rapid snowmelt or provide a good volume of food sources for animals.

Foresters have been working on treatments to deter the mountain pine beetle by attaching packets of a natural chemical pheromone called Verbenone, which emits an odor that tricks the beetle into thinking the tree has already been infested.

GUIBERSON: With beetles, we can try to apply verbenone so we can deter. Fire exclusion is a tough one because it's real hard to get fire in those ecosystems. We did that in one of the stands we had in Dillon, here, and I think that was probably one of the only… It was the only one in Montana [for BLM], that I'm aware of anyways, that we were able to go through to do some type of a treatment there.

We've done a lot of planting. That's the way we're dealing with rust, is we're identifying trees we think are they're showing signs of being resistant to rust, and so we're collecting cones from them and growing them out, getting them tested to see if they have resistance. So that's been kind of probably our biggest impact, I would say, is trying to plant into those areas that have recently been burned by fire, or if there's, you know, high overstory mortality. Just trying to get something back in the ground that we know is going to have that resistance level for the site.

NARRATOR: Foresters and researchers have been working on active treatments to save whitebark pines in the US and Canada for many years. For BLM, a recent addition to the funding mix came through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which is making investments for ecosystem restoration. This has allowed Foresters like Emily Guiberson to add long-term monitoring to the checklist, to see whether the treatments are having an effect.

GUIBERSON: It's definitely expanded our ability to do more, for sure. One of the agreements that we've had for several years was with the National Park Service. They have a monitoring crew that's based out of Bozeman that has been doing this data collection for -- I think it's almost… it's over 20 years for sure. I don't know exact numbers on how long they've been at it. But it was something that we wanted to kind of get in on. And a few years ago, we started looking at what that would mean, because they go out -- they survey all areas within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, doesn't matter if it's Park Service, Forest Service, if it's federal -- they get there. So we worked really closely with them and USGS to get kind of this protocol in place that would allow us to attach on to what they had already started. And so we had everything ready to go. We just didn't have any way to fund it. And that was kind of the last piece of our -- I guess in my mind though whitebark puzzle for us.

This monitoring inventory piece of it was sort of the last one in because it wasn't as there wasn't as much urgency on that piece of it. So, we had this all, like, set up; we had no funding. And so that last piece that came in: the Dillon Field office, almost the entire office, is identified as one of the restoration landscapes in Montana. And because of the relationships set up already -- that partnership that's been ongoing for so many years -- it kind of segued us into this brand new agreement with the Montana Office to continue that work. They provide us all the data so that we can utilize it for [threatened species] consultation or if we are to ever consider delisting, we're going to have to be able to say, “this is what we have and this is what it looks like,” and we didn't have that before. So this data will help us get to that point where we can say, you know, statistically this is the condition of our stands.

HOWELL: One of the interesting things I think about projects like this is we're able to highlight the fact that BLM's not working in a vacuum, right? That (a) it takes a lot of time to get stuff up and moving. But (b) there's a lot of other people that are involved.

GUIBERSON: So many people, so many, and it's at all levels and I am very happy that we have the ability to lean on our other agencies. You know, like, the monitoring piece was something that was the very end of it because there's so much emphasis on managing that sometimes that it's the lowest priority.

HOWELL: And as you said, if you're going to get, if you're going to get the species delisted at some point, it's only going to be based on the science and the data that you have behind it.

GUIBERSON: And knowing that they've been doing it for as long as they have and it now the data will talk! You have data that talks, whereas before it was like, “Well maybe they did it this way over here, and maybe they did it this way over here, so it's not comparable data -- it's interesting data, but it doesn't speak to the whole range.” And so, I was really happy about that last piece to come in because, you know, we had all the other parts of it and then just going together forward, it just makes it all stronger.

NARRATOR: Long-term, the future of recovering the whitebark pine is uncertain. The good news is that the foresters who are studying the species are in it for the long-haul.

GUIBERSON: I just feel like anybody that has been involved in this, it's usually not because they were told they had to. It's usually because they start to look at it and then it like clicks that it's really important. and then they're involved in it their entire careers and then some! A lot of the people that even have retired out of this, are still heavily involved in it. So I guess I would just say that like, this is one of those things that like, gets into you and it changes you. And when you leave, you take it with you. It's not something that you leave at the door.

HOWELL: So it's a mission!

GUIBERSON: It is a mission for sure! And you know, just the partnerships that we've developed over the years and there's some of my closest friends because of how much we've worked on together and how much we've seen happen over the years. So it's a great group of peers and just overall good people that want to see change, and so that's promising.

NARRATOR: Emily Guiberson is BLM’s Forestry lead in the Montana/Dakotas State Office. She joined us from her office in Dillon, Montana.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Whitebark pine and the creatures that depend on it, I highly recommend you watch a video by the conservation group American Forests called “Hope and Restoration: Saving the Whitebark Pine” which is on YouTube. We have a link to it on our website for this episode, along with other stories we have published about this species.

Thanks for joining me! I’m David Howell, and we’ll see you out there "On The Ground."