Help pollinators, “bee” a community scientist

Listen

Subscribe

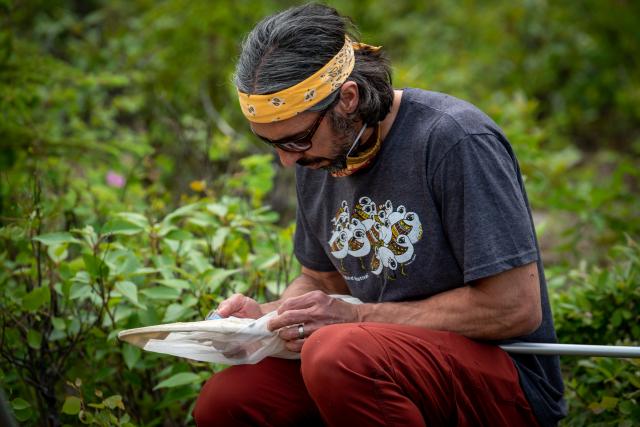

We're all abuzz about bees in this Frontiers podcast. BLM Alaska wildlife biologist Casey Jones recently sat down to talk about community science initiatives and how people can help us learn more about Alaska's bees.

Transcript

Photos and story

[Jim Hart]: Welcome to the BLM Alaska Frontiers podcast, I'm Jim Hart.

Called either citizen science or community science, the opportunity for people to help address real-world issues through science is all around. Training on proper techniques, or protocols, is included, and the data gathered could be used to make new discoveries, solve complex problems or create a more complete picture of the natural environment. BLM wildlife biologist Casey Burns recently sat down to chat about a community science initiative involving bees in Alaska. He's the BLM Alaska program lead for the Wildlife and Threatened and Endangered Species Program. And yes, there are some bees his program hopes to help. There are several projects that could be fed by the data gathered, but he was abuzz about one particular project, the Alaska Bee Atlas.

[Casey Burns]: Overall with the Alaska Bee Atlas Project, it's an interagency effort to collect and share information for our one hundred and four known bee species in Alaska.

Alaska, as you know, is a huge state with a very small road system, and there are a lot of places that are hard to get to. So, we are inviting citizen science, or community scientists, to join us in this effort and do the same protocol that our agency biologists are doing out in the field if they're out, especially in remote places.

Another thing we're doing, though, besides getting this inventory of these remote places, is setting up more routine monitoring in easier-to-get-to places, places that we know we can get to multiple times per year, every year, to get a more in-depth dive. So that actually is inclusive of a lot of people in our larger communities where we can get many people out to participate and to learn about bee monitoring and bee conservation.

So it's kind-of two pronged. We really are targeting the wild areas in Alaska, but we're also working in the more developed areas where the population is.

[Jim Hart]: It's pretty cool as a community scientist to know that once you collect the information, it doesn't sit on some shelf and collect dust, of course, in order for them to gather useful data for folks who don't work as biologists every day. The techniques have to be user friendly.

[Casey Burns]: The protocol that we're using is fairly simple. You don't need to be an entomologist just to do it. After the the sampling protocol is done, specimens are brought back to be identified by the entomologists at ACCS, and that's the Alaska Center for Conservation Science, our partner in this effort. So, they have the real technical expertise in identifying the bees, which can be quite challenging, and then the information shared back for everyone to use. There's a lot of important uses at the BLM for this, but a lot of other agencies or groups or individuals are interested as well. So, we put it out there for everyone to use.

[Jim Hart]: After centuries of studying and even domestication, don't we already know enough about bees?

[Casey Burns]: So, we know very little about the bee species and all the pollinators, especially many other pollinator species in Alaska. So, we're doing this to give us the basic information that we need to manage the species in their habitat in the state. The big driver for the BLM is we have five species of bumblebees that are considered BLM sensitive species in Alaska.

And what we're trying to do is manage them proactively to reduce the need to put those on the endangered species list. So we want to understand more about these species, where they are, what their statuses and trends are, what their associations are with different habitat types or different specific flowers, so we can understand potential impacts, avoid or minimize any negative impacts, and then potentially do proactive work as well to conserve these species.

In addition to the five BLM sensitive species, there's two species that are currently candidates for Endangered Species Act listing that are also thought to be in Alaska. And we're trying to understand more about their populations in the state as well.

[Jim Hart]: So, while we know Alaska has a whole bunch of bee species, it's what we don't know about them that drives community science.

[Casey Burns]: So, as I mentioned, we know so little about what we have right now in Alaska and bee information in general pollinator information around the world is is lacking. So, we're not the only ones here. Anything that we get pretty much as it's new information for us at this point and is useful.

Ashton cuckoo, Suckley's cuckoo, northern yellow, confusing, and Kluane.Photo by Lisa Gleason.

The most fascinating thing to me is when we keep finding new species and we've been working on kind of predecessors to this grander effort for a number of years and kind of developing this protocol. So, we have been out doing it and some of the partners have been doing it. It's amazing to me, you know, when we find species that are new to the state or even new to the continent, species that are more Eurasian that we didn't know we had, you know, we just have these vast landscapes out there that we just have very little baseline information on so many things, pollinators included.

[Jim Hart]: If helping scientists gather more information about bees has you buzzing with excitement. Casey told us they are looking to expand the program and they're looking for community science leaders who can help recruit and train local teams? Get in touch with Casey Burns to find out more by emailing him at [email protected]. He'll help you get dialed in and trained up so you can be a successful community scientist.

That's it for this podcast. Be sure to check out the BLM Alaska website and Facebook page for more information about community science initiatives and activities in your area [and check out the Alaska Center for Conservation Science website for more cool bee information]. The Frontiers podcast is a production of the BLM Alaska Office of Communications.