You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

BLM Wildfire Management Series

Part 1: America's Fire Problem

In the autumn of 1871, a small fire broke out on the O’Leary family farm in Chicago. By itself, this small incident was fairly unremarkable. But that was before it escalated into a 2,100-acre blaze responsible for destroying more than 17,000 structures and leaving more than 100,000 Chicagoans homeless.

At the same time, another fire was taking root in the forests surrounding Peshtigo, Wisconsin. Though overshadowed by the infamous events in Chicago that day, the Peshtigo fire tragically claimed five times as many lives and reduced approximately 1.2 million acres to ash.

Just across the lake, multiple other major fires were recorded in Michigan on the same day.

Though these catastrophes befell different communities, their causes were identical. The densely wooded region around Lake Michigan was at the tail end of an unusually long, hot, arid summer. For residents of Colorado and other parts of the west, those conditions – which are ideal for the uncontrollable spread of wildfire – may sound strikingly familiar.

Extreme conditions aside, naturally occurring forest fires have a surprisingly positive effect on healthy ecosystems. They help control parasitic insect populations, promote new growth, and provide renewed foraging for wildlife populations. They help remove sick and dying vegetation before blight can spread, and they create open spaces that stop the advances of larger, deadlier fires. They clear away brush and undergrowth that can choke forests, a feature that some trees – like the aspen – depend on for their survival. Because of these benefits, a common practice was to allow wildfires to run their natural course and burn themselves out. But after the Great Chicago Fire, that was soon to be the way of the past.

While building codes were rapidly revised to help slow the spread of urban blazes, wildfires continued to consume millions of acres of western landscape. By the turn of the century, suppression became the de-facto response to large-scale wildfires in Colorado and in the majority of the west. But deliberately halting a natural and vital element of forest ecosystems was not without consequence, triggering a cascade of devastating problems over the decades that followed.

As we became increasingly adept at suppression techniques, fire-deprived forests became increasingly overloaded with dead trees, brush, and grasses. Denser tree spacing then made it easier for insects and disease to spread, increasing the rate at which flammable biomass piled up. Eventually, suppression capabilities became so effective that it encouraged residential sprawl deep into Colorado’s forest and wildland areas – an exponential danger increase because more people and more property were now in high-risk areas, and because human activity is known to cause 70 percent of all wildfires.

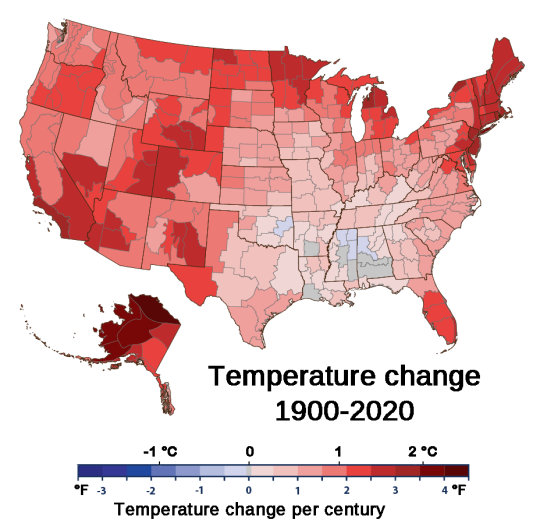

When combined with the effects of climate change, these inescapable realities have merged into the ever-present menace of catastrophic wildfire that now looms over public lands and local communities. But, under these unforgiving conditions, there are still those who dedicate themselves to combating that threat.

Part 2: Making Things Worse

John Markalunas is a firefighter with the Bureau of Land Management. As the fire management officer for the BLM Colorado Rocky Mountain District, he is responsible for mitigating the wildfire vulnerability of approximately 1.2 million acres of the forests, fields, and mountains that symbolize the state’s history. However, the impact of that history on the land, says Markalunas, permanently changed the course of wildfire in the region.

“In Colorado, and in the west, a lot of the [forests] became the same after settlement,” he said. “Because so many of trees were cut down.”

By clearing the landscape, humans inadvertently wiped out the biodiversity of those areas, as well as the natural mosaic of lifecycle stages that make up a healthy forest. Over time, the forests recovered. But, in propagating from such a drastically reduced population, the new growth was not only the same approximate age, it was also from extremely limited genetic stock.

“That creates a really unique set of problems and unique conditions for forest fires,” he added.

That problem – where the genetics of a given population are nearly identical – is referred to as a monoculture. Similar DNA means similar weaknesses to insects and disease; the dangers of that are well documented, from the Potato Famine in Ireland to the current state of forests in the American west. In Colorado’s forests, this is compounded by the unnatural growth density resulting from decades of fire suppression, creating conditions for acute transmission of disease and insect infestations – a substantial complication for Markalunas and his team.

“You’ll end up with a big insect outbreak on a timber stand. Or, a disease gets in there and it kills the trees. It’s like dead grass, but on a larger scale and much more problematic,” he shared. “You’ll have acres of dead trees. Usually on steep terrain.”

The unprecedented accumulation of flammable biomass in America’s forests eventually drove policy changes in the 1960s and 1970s designed to safely and effectively reduce the buildup. Through the intentional application of regulated, small-scale fires – called prescribed burns – land and forest management personnel could begin selectively clearing away problem areas by mimicking the beneficial functions of fire in the wild.

Today, combustible fuel overload management extends beyond the use of prescribed burns. The unique look of disease and insect-felled timber has found a place on the consumer market. Goats and cattle are being used to remove fire-prone underbrush through selective grazing techniques. Technological advances have improved detection and monitoring capabilities by orders of magnitude, allowing firefighters to identify and track fires in real time across thousands of square miles. Advances in weather modeling help predict fire movement and intensity, while new types of aircraft are providing real-time monitoring capabilities in previously unreachable areas. These, and more, show just how far the toolset has developed for those who face these issues on the front lines.

Yet, such incredible advances mean very little without personnel on the ground, because the best mechanism for preventing or suppressing large-scale wildfires remains rather low-tech by comparison.

Part 3: And Another Thing…

“Fire, itself, is a tool,” said Markalunas. “It’s one of the few tools that allows us to treat [wildfire] at scale.”

While prescribed burns are an effective means for wildfire management, there are limits on what can be accomplished by a handful of crews. A staggering level of combustible fuel buildup, an overwhelming number of acres, worst-case-scenario weather patterns, and dramatically increased human habitation encroaching on high-risk wildland areas have created a treacherous maelstrom of obstacles for wildland firefighters.

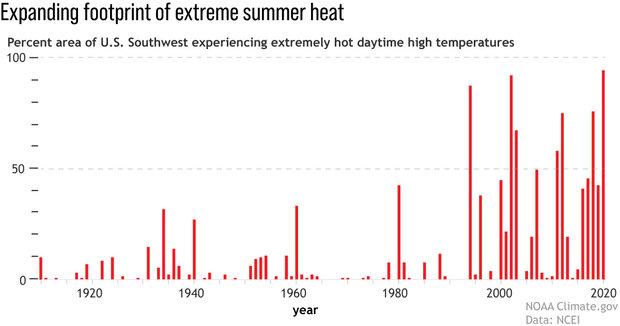

“In my career, I know that fire seasons have gotten longer. Instead of a May to September season in Colorado, our season now goes from March to November,” he said. “We also have more fires than we used to. And, they’re all getting larger.”

The impact of these seasonal shifts, when combined with an escalation of complicating factors, have made manpower the most critical element in the efficacy of prescribed burn programs. In the past, with more regular and pronounced seasonal changes, fire crews required staffing approximately 220 days a year. Now, that number is closer to 365.

“We generally aren’t staffing for fires in the winter like we are in the summer,” said Markalunas, who also said his staff would be reduced by 60 percent once seasonal employees were furloughed for the winter.

To address the growing staffing needs of the wildland firefighting community, a common practice has been for nearby agencies to supplement one another’s rosters. But the limitations of that solution are becoming unmistakable. With year-round operations, the shortages created by a seasonal staffing model leave crews stretched thin, bone-weary, and unable to lend support where and when it is needed.

Unfortunately, ideal conditions for prescribed burns arrive where the frantic end of wildfire season overlaps with the furlough of seasonal staff. Consequently, when increasingly rare opportunities arise for a burn, mustering the manpower requires a spectacular effort – often, to treat only a fraction of the desired acreage. This, of course, depends on cooperation from the weather – and, the weather in the 2022 burn season was less than accommodating.

Because the conditions to safely conduct prescribed fires are so precise, any delay can substantially shorten the burn season. Unusually high rainfall during Colorado’s spring and early summer soaked the forests, adding delays while the terrain dried out. By the end of the season, storm fronts were pushing weather across the range, generating high winds and volatile burning conditions as winter began its approach. For Markalunas and his team, reality settled in; they may be done for the year.

- John Markalunas, Fire Management Officer, Bureau of Land Management

Part 4: Deer Haven

Temperature: 67 degrees. Precipitation: zero. Wind speed: 7 miles per hour out of the southwest. Relative humidity: 23 percent.

Fire engine captain Damon Kurtz – a member of Markalunas’ staff – has an acutely developed appreciation for the value of prescribed burns. When a 10-day forecast hinted at a narrow window of opportunity to treat some final acreage near the Deer Haven area, Kurtz was one of the first to notice.

“So much land needs to be treated, and it takes so long to do it, and we have so few resources… if we can make a difference, we need to do it,” said Kurtz.

Part of making that difference is the delicate work of accounting for the weather, as even small fluctuations can determine if a burn will commence. Kurtz knew any forecast so far out was almost certain to change. But he analyzed whether it might be possible to fit one last burn within the exacting parameters required for prescription. The calculations were complex. But, if the weather held, it looked like they had a real chance.

Over the next several days, Kurtz watched the weather and crunched the numbers. As the window for an optimal burn approached, the weather held steady enough to give Kurtz grounds for cautious optimism. But he would need to make his case – and fast – if the team was to have any hope of coordinating the resources in time.

“With prescribed burns, there’s risk involved and it’s easy to find a way to say ‘no’,” said Kurtz.

The difficulty of burning late in the season comes down to several factors. It is the driest time of the year and is often threatened by high winds. With fire-quenching rains and snows on the heels of those winds, the anticipation of moisture can tempt some to see an added advantage to attempting a burn. Seasoned firefighters, however, recognize that temptation and try to ensure it is not a factor when deciding to treat an area.

"The weather and fire behavior forecasts were on the higher end of the prescription. Some were more comfortable with this than others, but since prescribed burns are so necessary to reduce hazardous fuels and decrease the risk of catastrophic wildfires, we need to maximize our production with so few burn windows."

Every prescribed burn must overcome an incredibly complicated approval process that involves multiple layers of control, several dozen extremely narrow environmental metrics, multiple administrative committees, myriad regulatory requirements, resource and funding analysis, long-term land management planning, and the tangible complications that come with the simple logistics of physically executing an operation with so many moving parts.

But, with the weather holding – and Kurtz’s assessment showing promise – Markalunas knew he had to position his team to take advantage of the late-season anomaly. Tentative preparations soon began, setting into motion the impossibly intricate mechanism that is a prescribed burn.

Part 5: Unforgiving Precision

Bob Lang owns a small ranch nestled between the rolling hills and mesas of Fremont County, a few miles northwest of Cañon City. Lang, a long-time resident of Colorado whose property lies just across the valley from the Deer Haven trailhead, has seen both the raw power of large-scale wildfire and the difference prescribed burns can make.

“In this country, the wind can change. It can pick up from a gentle breeze to 30 miles per hour in no time,” he said. “Prescribed burns are a bit of a double-edged sword from my point of view: they’re necessary, but you’re playing with fire.”

Lang’s concerns have some merit; when a planned ignition escapes its intended boundaries, it can pose a significant threat to the surrounding area. Fortunately, fewer than one percent of all prescribed burns ever cross into unintended locations. Even then, it is rare for an escape to grow into something more than the firefighting team can handle.

Such an astounding success rate is due, in large part, to a complex planning and approval process, with each burn tightly controlled and continuously monitored until the threat of spread no longer exists. But a prescribed fire’s success has little to do with what happens during the burn.

Much like some other government agencies, the true successes of BLM firefighters are invisible. They can only be measured by that which does not happen. Unfortunately, public perception of fire treatment programs can often be shaped by the exceedingly rare and highly publicized instances where an operation does not go exactly according to plan.

“This year, they had a number of escaped burns in the Forest Service. That basically shut down large programs and hurt our trust with the public,” said Markalunas.

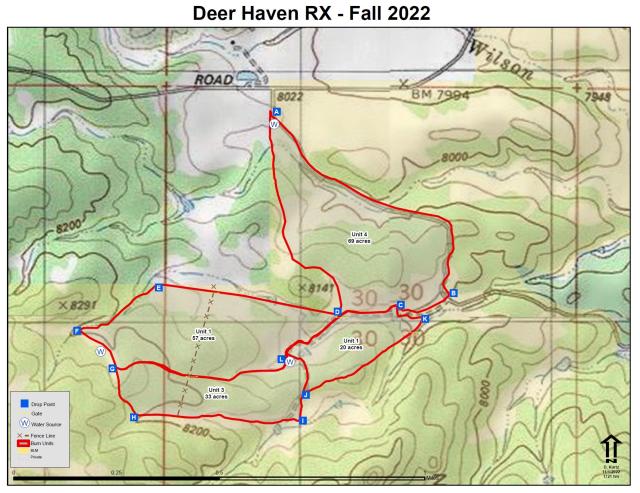

Anything less than a perfect delivery could jeopardize the program. Assigned as the Deer Haven project burn boss, Kurtz felt that responsibility weigh down upon his shoulders as he set to planning a 177-acre treatment – a number, he said, was based on several factors.

“Deer Haven has been on the docket for a while,” Kurtz said. “After calculating for elevation, fuels, humidity, winds, and everything else, it fit our remaining resources.”

But the weather reports continued to roll in, and the projections began to shade the effort with some doubt. The team might be faced with conditions on the upper end of prescription, which would add substantial difficulty and risk to the burn.

“I didn’t sleep the night before. Was I being too aggressive? Will the winds shift or change speed?” Kurtz asked. “If things go sideways, will we have enough people on hand to control it?”

As the day of ignition dawned, Kurtz gathered his things and drove to the office, his questions still unanswered

Part 6: Be Careful What You Wish For

Spot forecast for: Deer Haven RX… Colorado BLM Rocky Mountain District Fire.

From: National Weather Service… Pueblo, Colorado.

Time: 5:51 a.m., Daylight Mountain Time. Wednesday, November 2, 2022.

As the report sizzled across the wire, it gave Kurtz and his team their first good look at what they would be facing that day: 20-foot winds gusting at up to 30 miles per hour, and relative humidity bringing the burn area to near-critical fire weather conditions. The complexity created by those conditions might now require more manpower for the burn to be conducted safely. But, manpower was one resource in critically short supply.

“Fall is the end of the fire season, and people are exhausted,” said Kurtz. “There are firefighters with more than 1,000 hours of overtime.”

Wind conditions had been raising questions with the team all that week. Now at the point of the year where many agencies were losing seasonal manpower, he understood additional assistance was a less-than-remote possibility. As he prepared for the morning brief, Kurtz did so knowing the entire burn was at risk of being called off. But he still held out hope.

“Wind potential was on the upper end of prescription range. But the winds that were actually predicted were on the upper end of the desired range,” said Kurtz, drawing a distinction that justified that hope.

The burn crew, however, still had questions. To help settle those questions, the team looked to the expertise and leadership of Norden and Markalunas.

“We’re a very small organization, and we don’t always see eye to eye. There are different opinions. There’s no groupthink,” said Norden. “But, after considering a broader range [of dates,] we knew Wednesday was the best day to burn.”

But, by Wednesday, it had become clear they were going to need help beyond what was already being provided by the Rio Grande National Forest, the Pike San Isabel National Forest, the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control, and the Tallahassee Fire Protection District. It had become clear they needed to reconsider their approach.

They shifted gears, conducting an analysis of their resources and which factors were within their control. An earnest and highly technical debate ensued, regarding the various factors governing prescription parameters and, before long, possible solution emerged.

“We had a good number of acres already accomplished for the year,” said Norden. “So, the question wasn’t as black-and-white as ‘yes’ or ‘no’. It was more ‘to what extent’.”

In that line of thinking, Markalunas and his team managed to reach a consensus by scaling back their acreage to fit available resources, rather than trying to find additional resources to treat the acreage.

“We still need to do what good can be done. This area has been waiting [to be treated] for seven years,” said Norden.

Part 7: The Last Burn

By 9 a.m., the team had set their markers and staged their water points. Equipment had been checked and drip torches filled. All vehicles were fueled. Neighboring agencies were on hand to assist, and the weather was holding. The crew was ready. The order was given. Ignition commenced.

Then, mere minutes into the burn, the variability inherent to any Colorado forecast finally reared its head. Gone were the steady breezes of the last week. Replaced by an abruptly shifting wind, the direction of the fire’s travel became erratic, shifting abruptly.

Seeing smoke from his ranch across the valley, Bob Lang rushed toward the source, fearing the worst. As he carefully approached a wide wall of smoke, he found personnel from multiple fire departments already on the scene and BLM personnel happy to answer his questions.

“From a landowner or land user’s point of view, BLM is probably the easiest group to work with,” he said.

Recalling the last prescribed burn at the site, Lang continued.

“I’ve run into BLM guys back in Deer haven and said, ‘I ought to keep an eye on these guys and where they’re laying their fire’,” Lang recalled. “But they were right on it.”

Lang’s trust was well-placed. For the next several hours, Kurtz and his crews compensated for the changing winds. They carefully redirected the fire to keep it within the prescribed area, while also selectively preserving vegetation that would encourage future healthy forest growth.

“The wind was high and it shifted a lot more than expected,” said Norden. “But there were no failures or problems.”

By the end of the day, clusters of trees stood safely preserved in rolling fields of pitch black – an ideal outcome for a prescribed burn, according to Markalunas. He further explained that clearing these spaces helps to bring back meadows, which preserve and improve habitat for numerous types of wildlife essential to the ecosystem.

“If you came back here in the spring, you’d be amazed at the wildflowers that will pop up,” he said. “I mean, even tomorrow you’d be likely to find some deer or elk in here.”

That resilience is only possible when the landscape is not being choked out by various underbrush and decades-long buildup of flammable materials, he continued. In highlighting the importance of prescribed fires to the ecosystem, Markalunas was also quick to credit the success of the burn to the neighboring agencies that sent help when his team needed it.

“On this burn, we have two [National] Forests, our home BLM unit, the state [of Colorado], and a cooperating fire department all helping out today. And, they all came together with fewer than 48-hours’ notice to implement this project,” he said.

Part 8: What We’re Willing to Live With

For the dedicated individuals in this career field, success depends on the ability to create opportunities where none exist. Accomplishing a burn so late in the season is just one display of the creativity and perseverance necessary to those who manage fires on public lands. But there is another source of heat wildland firefighters must manage – one their work cannot subdue, one increased with each burn they tackle.

Prescribed burns have enjoyed broad support in many communities. In others, some have begun to question that support. But, as part of a larger conversation about wildfire management, Markalunas and his team believe it is important to discuss the benefits and risks associated with fire treatments – especially in an era where the climate is rapidly changing.

“Climate change isn’t going away. Fires aren’t going to trend downward any time soon. On some level, we need to understand that fire is a part of the ecosystem,” Kurtz said.

Markalunas agreed.

“It seems as if we’re expected to manage only for suppression – but, not so much for forest health and wildlife – when they’re all interconnected,” said Markalunas. “Wildfire is a natural part of the ecosystem. Until it can play its part, the system will remain out of whack.”

“Focusing on suppression is how we got here in the first place,” he added.

Kurtz believes a better public understanding of prescribed fire programs can effectively highlight their benefits to the environment and, by extension, an economy so heavily dependent on outdoor activity.

“A little bit of intermittent smoke in the fall and spring is better than heavy smoke all summer, every summer,” he said. “I’m not sure the public understands all the benefits prescribed fire brings. It has a direct impact on hunting and fishing, every kind of outdoor recreation, wildlife habitat, air pollution, tourism, and even homeowner’s insurance rates.”

Targeted, relevant, public information can play a substantial role in making that happen, said Markalunas – even as the challenges of the political climate add another layer of complexity for those braving the dangers of the fire line. His reason for optimism lies in recent provisions included in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

“I see some hope that wildland firefighting is now being recognized as the full-time profession that it is. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law has started the conversation by improving pay to be more commensurate with the skills and experience the job demands.”

With the beginning of that conversation, both Markalunas and Kurtz see an opportunity for the American public to recognize the situation as a priority, and for the possibility of implementing meaningful policy to protect the environment, wildlife, homes and businesses, and even the lives of the people they serve.

But, for Kurtz, the entire situation can be boiled down to a simple proposition.

“The real question is what kind of fire we’re willing to live with – large and devastating, or moderate and manageable. If I could get people to understand just one thing, that would be it."

Attachments

Related Stories

- BLM Fire Team brings Smokey Bear to Kingman’s Street of Lights

- Rural wildland firefighting partners grateful for BLM gift

- BLM hosts fire investigation training course to strengthen wildland fire investigation capacity across Arizona and the West

- Helping Woodlands & Fighting Fire with the Dawson Project

- BLM delivers on administration priorities

Office

3028 E. Main St

Canon City, CO 81212

United States