You are viewing ARCHIVED content published online before January 20, 2025. Please note that this content is NOT UPDATED, and links may not work. Additionally, any previously issued diversity, equity, inclusion or gender-related guidance on this webpage should be considered rescinded. For current information, visit https://www.blm.gov/blog.

2022 | Next steps for greater sage-grouse conservation

In 2015 the BLM adopted plans for managing sagebrush-steppe lands in 10 Western states to conserve these public lands as habitat for the greater sage-grouse (C. urophasianus). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that the actions in these plans and others that cover private, state and other federal lands were enough to ameliorate the primary threats the species was facing, so that a listing under the Endangered Species Act was not warranted.

While the 2015 plans are a solid foundation for avoiding the need to list greater sage-grouse, we are interested in learning whether there are additional steps we can take to improve outcomes for sage-grouse going forward. As the steward of the largest share of remaining sagebrush habitat in the U.S., the BLM plays a key role in sage-grouse conservation. We are committed to reversing long-term downward trends in sage-grouse populations and habitats in ways that fulfill our multiple-use and sustained-yield mission and meet the needs of Western economies.

We are now reviewing the 2015 plans to focus on clarifying and updating them to account for relevant information that has become available since 2015, including new science and rapid changes affecting public lands such as the worsening effects of climate change.

By the numbers

The BLM is responsible for about 67 million acres of sagebrush habitat, more than any other surface-manager in the U.S. This gives the agency a leading role in efforts to reverse declines in sage-grouse populations by safeguarding the landscapes they and more than 350 other species rely on. Under our mandate of multiple use and sustained yield, we also manages these lands for the present and future benefit of people who rely on them to support livelihoods and traditions.

In the U.S. and Canada, state or provincial governments manage wildlife populations in their respective jurisdictions. Wildlife habitat is the responsibility of the person or group who owns the land or waters. Since the very beginning of sage-grouse conservation efforts, it’s been clear that coordination and collaboration among landowners and between various levels of government are essential to success because populations and habitats are biologically connected, irrespective of ownership.

The BLM has decades of experience in collaborating this way. The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA; 1976) establishes the principles of multiple use management for the 245 million acres of public land the agency administers and calls for public involvement in planning how those lands are used. Policies and regulations give the Act legs in everyday operations.

activities and structures associated with other authorized uses. Here, a BLM

crew removes an old fence that cut through sage-grouse habitat but was no longer needed. | BLM-Wyoming

As is true of any wildlife, sage-grouse do not acknowledge land ownership status or administrative boundaries, and their season-based lifecycles typically involve wide areas at different times of the year, for different uses: mating, nesting, brood-rearing. Responding to downward trends in populations or habitat conditions must be an all-hands effort, with an eye on the landscape level. The habitat under BLM stewardship – a 45% share – is wide and varied enough to provide much-needed monitoring data and places to utilize various science-based management tools to support conservation.

To the letter

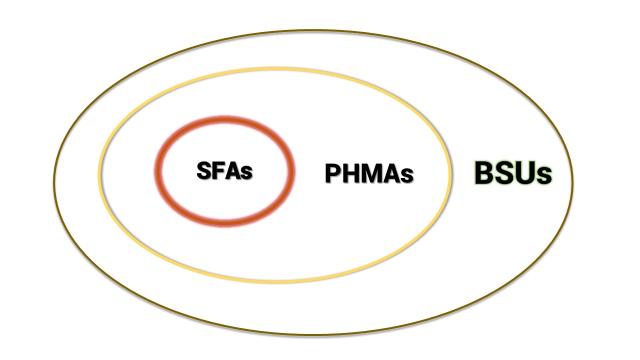

To guide the BLM’s on-the-ground conservation actions, the plans designate several categories of habitat. These designations inform decisions on authorizing proposed land uses and prioritizing investments in restoration and protection.

Priority habitat management areas (PHMA) are public lands that have the highest value for sustaining sage-grouse populations. Currently, 30.3 million acres of BLM-administered public land in 10 Western states are designated as PHMA.

Within PHMA, some acres (about 11.3 million) are singled out as essential strongholds and are designated as sagebrush focal areas (SFAs). The 2015 plans call for withdrawing SFAs from location and entry under the United States mining laws, subject to valid existing rights, to further protect their habitat values. The BLM will publish a separate draft environmental impact statement (EIS) analyzing the effects of the proposed withdrawal in late 2024.

The largest designation category, spatially speaking, is BSU, biologically significant unit. The management tool called a disturbance cap is tracked within BSUs to help ensure that habitat loss due to human activity does not exceed what sage-grouse can tolerate.

In light of new scientific information and ongoing climate change effects, we are considering whether there are additional steps we should take to improve outcomes for sage-grouse and for people across the West who rely on sagebrush-steppe for their livelihoods and traditions: How best to identify, manage and conserve sage-grouse habitat on public lands?

We’re planning for today and for the future.

Visit https://eplanning.blm.gov/eplanning-ui/project/2016719/510 for background information and documents.

Heather Feeney, Public Affairs Specialist

Related Stories

- “Where did my horse come from?” BLM launches a new way for adopters, trainers and others to learn about their wild horses and burros

- Lake Havasu Fisheries Improvement Program is the gift that keeps giving

- BLM is thankful for public lands volunteers

- BLM Fire and National Conservation Lands managers collaborate to meet shared goals

- BLM delivers on administration priorities